The origins of Montacute and its name

(Black and white image of the Tower viewed from Middle Street, from the Historic England website, accessed 21.11.2021).

Historical records show that the village has predominantly been known by three names or their derivatives: Montacute, Bishopston, and Logor’s Beorg. The name Logor’s Beorg, and its variations, may date back to the 7th century.

Logor’s Beorg

Montacute now derives its name from the hill that dominates the village landscape. The Latin phrase "mons acutus" translates to "sharp" (acutus) and "hill" or "mountain" (mons). However, prior to the Norman era, the village likely bore a very different name—something like Logorsberg. A.G.C. Turner’s “Notes on Some Somerset Place-Names” records various forms of the name, including Logderesbeorgum, Lodegaresbergh, Legperesberh, Loggaresbeorg, and Legderesbeorgum.

The word Beorg (or Burg) is an Old English term meaning hill, mound, or mountain, reflecting the village’s topography. But what about Logor?

Who or What Was Logor - an Arthurian Connection?

According to William of Malmesbury (who may have been born nearby in Sherborne), the village name as Logweresbeorh/Logorsberg is linked to a figure named Logwor, supposedly one of the twelve original monks at Glastonbury during St. Patrick’s arrival in the 5th century. In about 1127 Malmesbury says “It can certainly be maintained that Logwor is he after whom Logweresbeorh, now Mons acutus, is named”. This passage is found in Malmesbury’s De Antiquitate Glastonie Ecclesie and his Gesta Regum Anglorum; it refers to an inscription on one of two stone 'pyramids' by Glastonbury Church, between which the grave of King Arthur was discovered in 1191. See bottom of page for the full passage.

Interestingly, Logor may also be connected to "Lloegyr"—the medieval Welsh name for a region of southern Britain. In fact, forms of the word like Logres and Loegria are found in Arthurian legend, referring to the realm of King Arthur. Could Logor’s Beorg be a reference to this mythical land? It is a fascinating possibility.

Thomas Gerard of Trent, writing in 1633, proposed a different theory. He thought that William of Malmesbury’s references to Logwersbroch and Legiosberghe might suggest a Roman Legion camp linked to the nearby Fosse Way. There's no real way of knowing if he got it right.

There are no names in the village today that might hint at a connection to "Logor". The closest I've found is in the name of the fields to the north of Montacute Hill, now home to the football pitch and cricket grounds. On a reconstruction of a 1782 map by Samuel Donne, these fields were labeled Higher Lossells and Lower Lossells. But apart from both starting with "Lo" the word "Lossell" doesn’t closely resemble "Logor". Also I’ve found no link to a surname 'Lossell' to explain the name of these fields, but interestingly JP recalls that these fields were once called Lost Souls—possibly a reference to unconsecrated burials or even the 1069 Battle of Montacute Castle. Although according to Wikipedia, the dead from that failed revolt against the Normans were buried in Under Warren, southwest of the hill. The original source for this information remains elusive.

Does the name Logor's Berg have Roman or Celtic origins?

What we do know is that versions of Logor’s Berg have previously been in use as the village name but we don't know how far back that goes. It is difficult to know if place names have been updated when manuscripts are transcribed. But in the surviving copies of De Antiquitate Glastonie Ecclesia (The History of Glastonbury Church), originally written in Latin in 1127 by William of Malmesbury, the transcription of a 7th-century charter records “On King Baldred who gave Pennard and Montagu – In 681 AD King Baldred gave 6 hides at Pennard, 16 hides at Logworesbeorh and fishing rights to the Parrett to Abbot Haemgils”. This combines the ancient name of Logor's Berg with Montagu, the later French derivative of the Latin Mons Acutus, which gives rise to the current name of Montacute, and could place the name 'Logor’s Beorg' in the Celtic era.

Bishopston

Sometime during the 9th century, the village we now know as Montacute was known as Bishopston. The name probably derives from 'Bishop's tun' where tun means settlement or village, but in William of Malmesbury's 12th century Gesta Pontificum Anglorum it mentions stone crosses erected by a Bishop and referred to as 'biscepstane', so it is also plausible that Bishopston, (written as Biscopestone in the Domesday book) could derive from 'Bishop's stone'. Whatever the etymology, this name change might have been tied to Tunbeorht, who is believed to have held dual roles as both Abbot of Glastonbury and Bishop of Winchester (Turner’s “Notes on Some Somerset Place-Names”). Glastonbury Abbey's connection to the land was strong, though it likely lost its claim during the Danish conquest of 1016 (The Victoria History of Somerset Vol II, Abbey of Glastonbury pp 82-89 and The Priory of Montacute pp 111-115).

Enter the Legend of the Holy Cross: Sheriff Tofig (Tovi), King Cnut's standard-bearer, made a remarkable discovery around 1035—relics, including the Holy Cross, at 'Lutgaresbury' (another version of Montacute's previous name, Logor's Beorg). Tovi handed over his lands to the church, and the village’s name reverted to Bishopston, emphasizing its religious importance.

Following the Norman Conquest, Montacute's fate shifted once again. William the Conqueror granted the land to his half-brother, Robert, Count of Mortain, who built a formidable motte and bailey castle on Montacute hill, designed to "overawe the district around" (The Two Cartularies of the Augustinian Priory of Bruton and the Cluniac Priory of Montacute in the County of Somerset; The Somerset Record Society, 1894). In exchange for the Montacute Priory, the monks of Athelney received Robert of Mortain's manor at Purse Caundle in Dorset.

By the late 11th century, Robert's son gifted Montacute's church, castle, burgh, market, and the manor of "Biscopestune"—complete with its hundred and mill—to the Abbey of Cluny, as recorded in A History of the County of Somerset (1911, pp. 111-115).

Monte Acuto: Evolution of the Modern Name

The name Montacute has its roots in the Latin "mons acutus" (meaning "sharp hill") and the French "montaigu," which later evolved into the Anglicized forms "Montagu" or "Montagud." This blend of Latin and French influences reflects the village’s rich history and its connection to the Norman Conquest.

In the years following the Conquest, both "Bishopston" and "Montacute" were used to refer to the village and the hill. Montacute likely originated as the local name for the hill, while the village was officially called Bishopston. In the Exon Domesday (1085) it says Robert Mortain's estate is called Bisopestona and 'within that estate is the Count's castle called Monagut' (see images below) The village appears as "Biscopestone" in the finalised Domesday Book of 1086, with the castle on the hill referred to as "Montague". Though the village’s name changed over time, "Bishopston" endured as the name of a tithing and persists today in the name of the street that runs north from the village church.

The name of Montacute for the village seems to have gained prominence after the Norman Conquest. This was probably because Robert of Mortain, half-brother to William the Conqueror, gave custody of Montacute Castle to his trusted companion Drogo de Montagu, whose Latinized name is "Drogo de Monte-Acuto." Drogo hailed from Montaigu-les-Bois in Normandy and was rewarded with significant holdings in Somerset. His influence remains in the names of Sutton Montagu and Shepton Montagu, two manors he held in 1086, with the latter serving as his primary residence.

According to the Duchess of Cleveland’s The Battle Abbey Roll (1889, Vol. 2, p. 284), Drogo had "come to England in the train of the Earl of Mortain, and received from him large grants of lands, with the custody of the castle, built either by the Earl or his son William, in the manor of Bishopston, and styled, from its position on a sharp-topped hill, Monte Acuto". So the name of the castle's custodian plus its commanding position on a "sharp-topped hill" led to the enduring name "Monte Acuto," now Montacute.![Image: a scene from the Bayeux Tapestry showing Robert (Rotbert), Count of Mortain (right) sitting to the left of his half-brother William, Duke of Normandy. Robert's full brother Odo (Odo Ep[iscopu]s, "Bishop Odo") sits to William's right, implying his seniority. (From Wikipedia, October 2021)](https://files.cdn-files-a.com/uploads/5688745/2000_6179d77ec8610.jpg) Above, a scene from the Bayeux Tapestry showing Robert (Rotbert), Count of Mortain (right) sitting on the left side of his half-brother William, Duke of Normandy. Robert's full brother Odo (Odo Ep[iscopu]s, "Bishop Odo") sits to William's right, implying his seniority. [Robert took custody of Montacute after the invasion].From Wikipedia, October 2021

Above, a scene from the Bayeux Tapestry showing Robert (Rotbert), Count of Mortain (right) sitting on the left side of his half-brother William, Duke of Normandy. Robert's full brother Odo (Odo Ep[iscopu]s, "Bishop Odo") sits to William's right, implying his seniority. [Robert took custody of Montacute after the invasion].From Wikipedia, October 2021

Domesday Records: Montacute and Bishopston

In this section, you'll find detailed translations and transcriptions of references to Montacute and Bishopston from the Exon Domesday notes of 1085 and the Domesday book of 1086, alongside images of the original texts. These documents provide a fascinating glimpse into the landscape, ownership, and resources of Montacute during the late 11th century. The references include information on land holdings, taxes (geld), and key figures such as Robert of Mortain and his tenants. For clarity, I’ve also included a glossary of terms from the Domesday Book to help interpret these historical records.

References in the Exon Domesday (Liber Exoniensis)

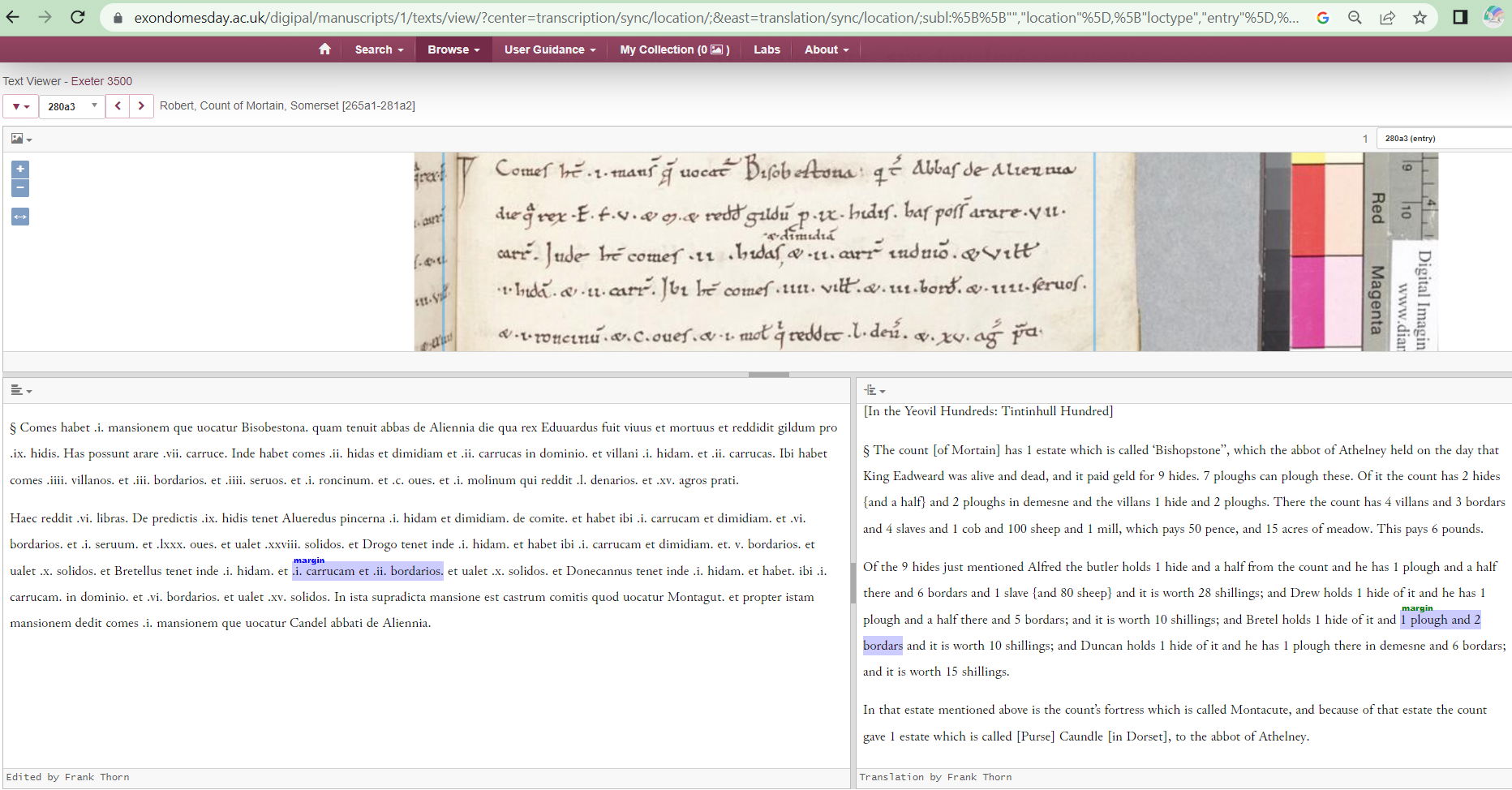

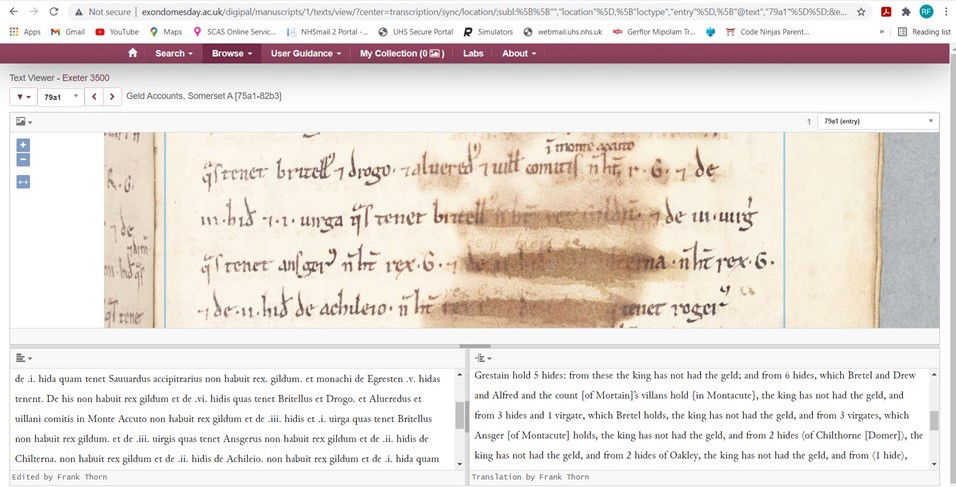

Images below: Montacute and Bishopston references transcribed and translated in the Exon Domesday in the Fief lists and in the Geld Accounts:

Bishopston in the Exon Domesday: The full translation reads:

§ The count of Mortain has 1 estate which is called ‘Bishopstone’’, which the abbot of Athelney held on the day that King Eadweard was alive and dead, and it paid geld for 9 hides. 7 ploughs can plough these. Of it the count has 2 hides and a half and 2 ploughs in demesne and the villans 1 hide and 2 ploughs. There the count has 4 villans and 3 bordars and 4 slaves and 1 cob and 100 sheep and 1 mill, which pays 50 pence, and 15 acres of meadow. This pays 6 pounds.

Of the 9 hides just mentioned Alfred the butler holds 1 hide and a half from the count and he has 1 plough and a half there and 6 bordars and 1 slave and 80 sheep and it is worth 28 shillings; and Drew holds 1 hide of it and he has 1 plough and a half there and 5 bordars; and it is worth 10 shillings; and Bretel holds 1 hide of it and 1 plough and 2 bordars and it is worth 10 shillings; and Duncan holds 1 hide of it and he has 1 plough there in demesne and 6 bordars; and it is worth 15 shillings.

In that estate mentioned above is the count’s fortress which is called Montacute, and because of that estate the count gave 1 estate which is called Purse Caundle in Dorset, to the abbot of Athelney.

Montacute in the Exon Domesday: The full translation reads:

In Yeovil hundred there are 157 hides and a half.

From them the king has had 30 pounds and 7 shillings and 6 pence of his geld for 101 hides and 1 virgate.

And the king’s barons have 31 hides in demesne. Of these the count of Mortain has 18 hides and a half, and Roger de Courseulles 4 hides and 1 virgate, and Beorhtmær 5 hides, and Warmund 2 hides, and Ansger the Breton 1 hide and 1 virgate.

And from 1 hide, which Sæweard the hawker holds, the king has not had the geld; and the monks of Grestain hold 5 hides: from these the king has not had the geld; and from 6 hides, which Bretel and Drew and Alfred and the count of Mortain’s villans hold in Montacute, the king has not had the geld, and from 3 hides and 1 virgate, which Bretel holds, the king has not had the geld, and from 3 virgates, which Ansger of Montacute holds, the king has not had the geld, and from 2 hides 〈of Chilthorne Domer〉, the king has not had the geld, and from 2 hides of Oakley, the king has not had the geld, and from 〈1 hide〉, which Roger de Courseulles holds, and from 1 hide, which Duncan and his brother hold, the king has not had the geld, and from 1 virgate, which Drew holds, the king has not had the geld, and from 1 virgate, which Roger the Bald holds, the king has not had his geld.

And of this hundred Osbern holds from the bishop of Saint-Lô alias of Coutances 2 hides and 3 virgates, from which he has paid the geld in Lyatts hundred.

From this hundred 6 pounds and 15 shillings of the king’s geld remain due.

References in the Domesday Book

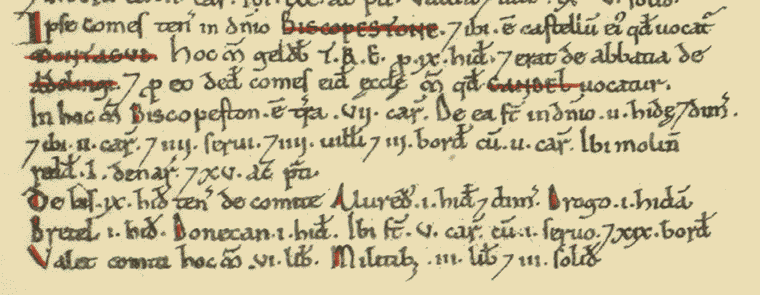

Image below; Bishopston and Montagu (references highlighted red) in the Domesday Book:

Literal translation:

Himself the count holds in demesne BISCOPESTONE (Bishopstone) and there is his castle which is called MONTAGUE (Montacute). This Manor paid geld TRE for 9 hides and it belonged to the abbey of ??? (Athelney) and for it the count gave to that church a manor which CANDEL (Purse Caundle) is called. In this manor Biscopeston there is land for 7 carucates. Of this in demesne 2 and a half hides and 2 carucates and 4 slaves and 4 villans and 3 bordars with 2 carucates. There is a mill rendering 50 denar, and 15 acres of meadow

Of these 9 hides holds from the count Alvred 1 and a half hides; Drogo (NB this name is translated as 'Drew' in the official translations) 1 hide, Bretel 1 hide, Donecan 1 hide. There are 5 carucates with 1 slave and 19 bordars. Value to the count of this manor 6L; to the Military (the knights?) 3L and 3s.

Translated by National Archives as:

The count himself holds in demesne 'BISHOPSTON' [in Montacute] and there is his castle which is called MONTACUTE. TRE this manor paid geld for 9 hides; and it belonged to the abbey of Athelney and for it the count gave to that church a manor which is called PURSE CAUNDLE [Dorset]. In this manor, 'Bischopstone', there is land for 7 ploughs. Of this 2 and a half hides are in demesne, and there are 2 ploughs and 4 slaves; and 4 villans and 3 bordars with 2 ploughs. There is a mill rendering 50d, and 15 acres of meadow.

Of these 9 hides Alvred holds of the count 1 and a half hides; Drogo 1 hide, Bretel 1 hide, Donecan 1 hide. There are 5 ploughs with 1 slave and 19 bordars. The manor is worth to the count 6L; to the knights 3L 3s.

The Open Domesday annotates the same tract as:

Land of Count Robert of Mortain

Households

- Households: 4 villagers. 22 smallholders. 5 slaves. (Bec's note - so a villager is a villan and a smallholder is a bordar; see glossary below.)

Land and resources

- Ploughland: 7 ploughlands. 2 lord's plough teams. 2 men's plough teams.

- Other resources: 2.5 lord's lands. Meadow 15 acres. 1 mill, value 4 shillings.

Livestock

- Livestock in 1086: 1 cob. 100 sheep. (Bec's note -Where does this come from???)

Valuation

- Annual value to lord: 9 pounds 3 shillings in 1086.

Owners

- Tenant-in-chief in 1086: Count Robert of Mortain.

- Lords in 1086: Alfred {the butler}; Bretel (de Sancto Claro); Drogo (of Montacute); Duncan, a man-at-arms; Count Robert of Mortain.

- Lord in 1066: Athelney (St Peter), abbey of.

DOMESDAY BOOK GLOSSARY:

Money:

l = libra, became a pound.

s = solidos, became a shilling

d = denarius, became a penny

Malmesbury's description of the Stone Pyramids of Glastonbury Church

Malmesbury proably incorporated a section about the two stone pyramids outside Glastonbury Church into his De Antiquitate Glastonie Ecclesie and then also updated his Gesta Regum Anglorum with the same information. In his 1981 translation of De Antiquitate Glastonie Ecclesie John Scott says of the section on the two pyramids “William incorporated this chapter, almost verbatim, into GR (Gesta Regum Anglorum), 25-6. Watkin (The Downside Review, 65 (1947), 30-41) discusses it and speculates as to the identity of the names in ‘The Glastonbury Pyramids'. For the latest archaeological findings see Ralegh Radford (‘Glastonbury Abbey’, in G. Ashe, The Quest for Arthur’s Britain, (London, 1968), 97-110). Some of the variants in the GR version of the description of the pyramids probably record William’s original work. The height of the pyramids is probably as recorded by GR because its better manuscript tradition makes it less likely to have been susceptible to the errors that could easily creep into the copying of Roman numerals. Centwine’s name ought to be read before that of Haeddi, as in the GR, because William was trying to preserve a complete record of the pyramids, whereas the reviser obviously transferred the name to the interpolated section of the previous chapter. We should read GR's Bregored et Beorwald abbates eiusdem loci tempore Britonum rather than DA’s Beorwald nichilominus abbas post Hemgiselum because the latter makes Beorhtwald, as the successor of Haemgils, an Anglo-Saxon whereas William described him as British."

So below I include the Latin text and Mynor's 1998 translation of the section on the Two Pyramids as found in Gesta Regum Anglorum:

Illud quod pene clam omnibus est libenter predicarem, si ueritatem exculpere possem, quid illae piramides sibi uelint quae, aliquantis pedibus ab aecclesia illa positae, cimiterium monachorum pretexunt. Procerior sane et propinquior aecclesiae habet quinque tabulatus, et altitudinem uiginti octo pedum: haec, pre nimia sui uetustate etsi ruinam minetur, habet tamen antiquitatis nonnulla spectacula, quae plane possunt legi, licet non plene possint intelligi. In superiori enim tabulatu est imago pontificali scemate facta; in secundo imago regiam pretendens pompam et litterae’ Her Sexi et Bliswerh; in tertio nichilominus nomina Wencrest Bantomp Winethegn; in quarto Bate Wulfred et Eanfled; in quinto, qui et inferior est, imago et haec scriptura: Logwor’ Weaslieas et Bregden Swelwes Hiwingendes Bearn. Altera uero piramis habet uiginti sex pedes et quattuor tabulatus, in quibus haec leguntur: Centwine Hedde episcopus et Bregored et Beorward. Quid haec significent non temere diffinio, sed ex suspitione colligo eorum interius in cauatis lapidibus contineri ossa quorum exterius leguntur nomina. Certe Logwor is pro uero asseritur esse de cuius nomine quondam Logweresberh’ dicebatur, qui nunc Mons Acutus uocatur; Bregden a quo Brentacnol et Brentemeirs; Bregored et Beorward*! abbates eiusdem loci tempore Britonum, de quibus et ceteris qui occurrere poterunt exhinc liberiori campo exultabit oratio.

"One thing generally unknown I would gladly tell, could I discover the truth, and that is, the meaning of those pyramids which stand on the edge of the monastic graveyard a few feet from the church. The taller, which is nearer the church, has five tiers, and is twenty-eight feet high. It threatens to collapse from old age, but still displays some ancient features, which can be deciphered though they can no longer be fully understood. In the uppermost tier is a figure habited like a bishop, in the second one like a king in state, and the inscription ‘Here are Sexi and Bliswerh’. In the third too are names, Wencrest, Bantomp, Winethegn. In the fourth Bate, Wulfred and Eanfled. In the fifth, which is the lowest, is a figure, and this inscription: ‘Logwor Weaslieas and Bregden Swelwes Hiwingendes Bearn’. The other pyramid is twenty-six feet high, and has four tiers, on which are inscribed Centwine, Hedde bishop, and Bregored, and Beorward. The meaning of these I am not so rash as to determine, but I suppose the stones are hollow, and contain within them the bones of those whose names are to be read on the outside. Certainly, it is maintained with perfect truth that Logwor is the man who once gave his name to Logworesburh, the present Montacute; that Bregden is the origin of Brent Knoll and Brent Marsh; and that Bregored and Beorward' were abbots of Glastonbury in the days of the Britons."